It may or may not be a coincidence that glass rhymes with class. All glass facades are synonymous with a clean, chic look, leaving viewers with a feeling of seeing something that is a cut above the rest. Not that long ago, we only primarily saw glass-dominated exteriors and interiors in high-end commercial office buildings.

That certainly isn’t the case today. Many residential and office towers in major cities now have floor-to-ceiling window-clad facades, lobbies, and all glass interior partitions.

Arguably, one of the most significant architectural innovations of modern times, however, has been the development of point-supported structural glazing systems as designers and engineers have pushed to create spaces with a minimal visual barrier between the interior and exterior, while maintaining structural strength and occupant comfort.

If you believe using glass is a new trend or just a phase, then it’s time to hit the history books. The use of glass in buildings dates back to the Medieval Times with stained glass for churches and cathedrals.

Since then, the fundamental purpose has remained the same – to allow light to enter a space and occupants to see out while providing a barrier against the elements. Today, glass does much more than provide natural light into a room or an enclosure to an office building, it’s making a statement.

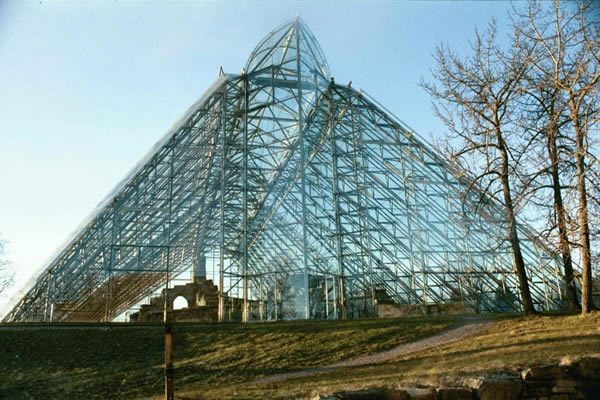

Now, structural glazing is widely specified for use in sports, retail, hospitality, and public sector developments large and small. It is also becoming increasingly popular in protecting heritage sites, where its low-profile, high tech fittings allow it to serve a practical function as an ultra-clear veil for preservation without obscuring or obstructing historic architectural features.

Leading this charge with the latest technology is the Pilkington Planar™system. In the 1960s, Pilkington developed the very first point-fixed structural glass system, the Pilkington Suspended Assembly System, which transformed the way glass could be integrated into the envelope of a building by removing the need to connect glass panels continuously to aluminum or steel framing.

Since the compressive strength of the glass is extremely high, frameless, point-supported systems flex under loading without any dynamic fatigue.

They tend to feature minimal fitting connections that enhance the overall transparency of the façade. High strength tempering helps to add additional strength to the glazing to span further between points of support.

As the designs for structural glass and complexity of back-up structures have advanced, the proportion of a building envelope that can consist of these glass systems has increased. Using this approach, systems can form minimally supported structural glass walls of great height.

The Pilkington Planar™ system – the successor to the Suspended Assembly System – has been used to create glazed surfaces taller than 230′ tall (70 meters). This is why it is the choice of many of the nation’s top glaziers such asW&W Glass, LLC.

The rapid development in glazing technology we have seen in recent years, and its incorporation into structural glazing systems in particular, has resulted in big steps forward in terms of what can be achieved. It’s not just aesthetically that glass has a leading role to play – it’s also vital to a building’s energy performance and the comfort of occupants.

Glass technology has advanced rapidly in recent years, and architects are now able to specify a range of high-performance products into these point-supported systems that enhance the building envelope, from triple-silver Low-e coatings that can be incorporated into triple-glazed insulating glass units (IGUs) that greatly improve energy-efficiency to interlayers that offer enhanced sound attenuation, structural integrity, and security properties.

The more advanced structural glazing systems become, the less visible metal is used in the design, allowing other architectural features to be showcased. For years, architects have stressed that less is more.

In the most contemporary projects, this means designers can create striking, light-flooded spaces with an almost outdoor aesthetic, with the added benefits of excellent insulation and shielding out excessive heat and glare from the sun.

Architectural glass is known for aesthetic properties – its unique ability to transmit, refract, and reflect light. As new manufacturing and coating technologies emerge, glass will begin to play a more active role in regulating the environment inside buildings.

Environmentally-responsive coatings would allow solar heat gain transmission to change throughout the day, and the seasons, in response to weather conditions. This would also bring aesthetic benefits, especially for windows that are only exposed to sunlight for a short period of time.

What if the glass could respond to the brief period of exposure by darkening, this would allow windows to deliver higher levels of transparency for the majority of the day? Does this sound familiar? This technology has, in fact, existed for more than 50 years and was first used in the lenses of eye glasses.

Microcrystalline molecules of silver chloride or another silver halide are embedded in the glass. These molecules are transparent in visible light without a significant ultraviolet component – artificial lighting, for example.

However, when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) rays in direct sunlight, the silver halide molecules undergo a chemical process that causes them to change shape and absorb a significant percentage of the visible light – so they darken. Once the glass is removed from strong sources of UV rays, the silver compounds return gradually to their transparent state.

This process has not yet become commercially viable at the scales needed for architectural glazing, but we could see this emerge in years to come. There is even the potential for glass to adjust its light transmission properties in response to air temperature, made possible by thermally responsive coatings – vanadium dioxide, for example.

There is also early development of angular selectivity coatings which can block summer light from higher angles while transmitting winter sunlight from lower angles.

This could allow problematic solar gain to be reduced without any change in the appearance of the glass from street level. In the meantime, there are commercially-available technologies on the market like electrochromic tintable windows and photo-sensitive interlayers that can lighten and darken to at least control sun glare and heat gain.

What about energy production? There are Building Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) products that can be readily integrated into structural glazing today. The goal for the future will be to continue to make it more transparent while improving its efficiency.

An ideal aesthetic for many architects is a free-standing wall of glass that provides physical separation while leaving the view completely unimpeded visually. To many, this would appear to be ultimate simplicity.

These systems are out there in the market, but are very expensive for tall spans (without any glass fins, cables, or steel back-up structural support), requiring very heavy glass make-ups, challenging fabrication, limited sourcing options, intense logistical coordination, and heavy custom equipment for manipulation and installation.

Will there be a way to increase the physical strength of the glass itself for these applications and reduce the thickness? Maybe at some point in the near future as emerging technology continues to develop, offering intriguing possibilities of what we may be able to soon achieve.